Nested Loops

Nested loops are a challenging technique in programming, yet one of the most versatiles ones. With nested loops we can scan through large and complex arrangements of data, perform repetitive tasks, compute useful and interesting formulas, etc.

A simple problem

Compute the sum of \(M\) integers, beginning with \(N\). For example, if \(M=5\) and \(N=0\), the sum to compute is

The relevant code is shown below and the full code is available on GitHub. A method takes two arguments, the beginning number \(N\) and how many subsequent integers to add, \(M\). Then it builds a loop beginning at \(i=N\) and continuing while \(i<N+M\). The last term that satisfies this condition is \(N+M-1\).

Thus to compute the sum \(0+1+2+3+4\), we must invoke rollingSum(0,5). Now, let’s say that for some weird reason we also wish to compute the following sums.

We will invoke the method RollingSum as follows:

rollingSum(1,5);

rollingSum(2,5);

rollingSum(3,5);

rollingSum(4,5);

Or, if we wish to be efficient, we can use a loop.

for (int k=0; k < 5; k++) {

rollingSum(k,5);

}

Now let keep the loop over k above but replace the rollingSum method with the actual code we used earlier:

for (int k=0; k < 5; k++) {

int sum = 0; // initialize sum variable

for (int i = k; i < k+5 ; i++) { // loop from k to k+5

sum = sum+i;

}

// print out the value of sum

}

A simple drawing

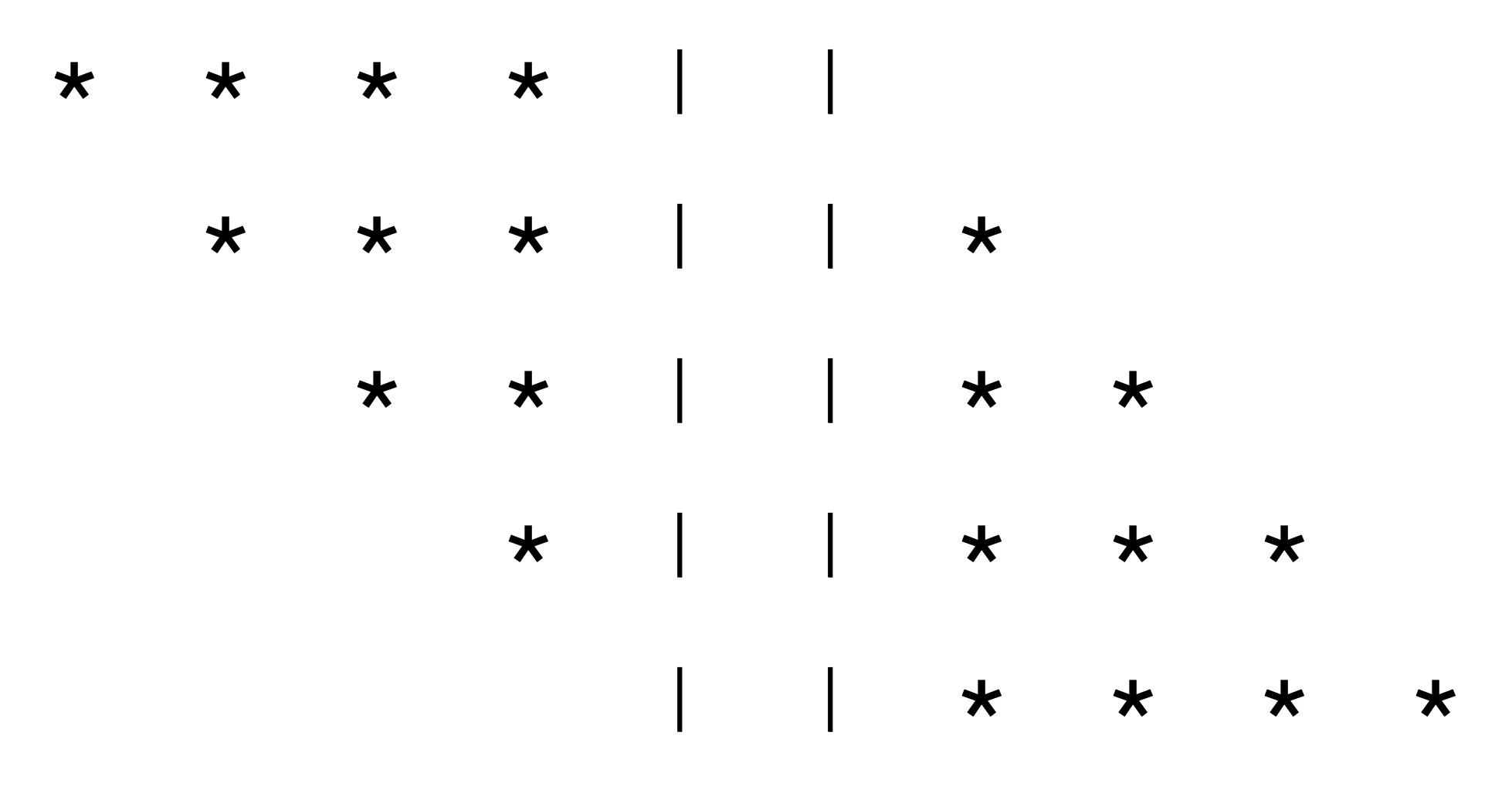

Suppose we wish to print the following pattern. The pattern comprises 5 lines. Each line has 4 groups of symbols: first a group of 0-4 spaces, followed by a group of 0-4 stars, followed by two vertical bars, followed by a group of 0-4 stars.

It helps to describe the groups of characters, line by line. Notice that even though it is not immediately obvious from the first line (Line 0), each line starts with spaces. It’s just that the first line has 0 spaces.

i |

Spaces |

Stars |

Bars |

Stars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Line 0 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

Line 1 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

Line 2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

Line 3 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Line 4 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

The first thing to notice is that the number of bars on each line is constant. The other numbers change from line to line. Specifically, we notice the following patterns:

the i-th line has \(i\) spaces;

followed by \(4-i\) stars;

followed by 2 bars

followed by \(i\) stars.

Where is that 4 coming from? It’s the number of lines in the pattern, minus 1. If we wish to print \(N\) lines, then we end up with \(N-1\) spaces at most, and that many stars. We can replace the number 4 above, with \(N-1\).

Let’s start putting the code together.

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

// print i spaces

// print (N-1)-i stars

// print 2 bars

// print i stars

// print a new line

}

How can we print \(i\) spaces, \((N-1)-i\) stars, etc? One way to do it is to use the repeat() method:

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

System.out.print(" ".repeat(i)); // print k spaces

System.out.print("*".repeat(N-1-i)); // print (N-1)-k stars

System.out.print("||"); // print 2 bars

System.out.print("*".repeat(i)); // print k stars

System.out.println(); // print a new line

}

We can achieve the same result with nested loops instead of repeat().

for ( int i = 0; i < N; i++ ) {

for ( int k = 0; k < i; k++ ) { System.out.print(" "); } // print k spaces

for ( int k = 0; k < N-1-i; k++ ) { System.out.print("*"); } // print (N-1)-k stars

System.out.print("||"); // print 2 bars

for ( int k = 0; k <i; k++ ) { System.out.print("*"); }// print k stars

}

Notice that the inner loops are written in a single line for simplicity. Each of the inner loops (i.e., those with loop variables named k) depends on the current value of the outer loop (the i variable). So, when \(i=0\), at the first iteration of the outer loop, the inner loops will run as follows:

for ( int k = 0; k < 0; k++ ) { System.out.print(" "); } // print 0 spaces

for ( int k = 0; k < N-1-0; k++ ) { System.out.print("*"); } // print (N-1) stars

// etc

In the second iteration of the outer loop, \(i=1\) and the inner loops will look like:

for ( int k = 0; k < 1; k++ ) { System.out.print(" "); } // print 1 spaces

for ( int k = 0; k < N-1-1; k++ ) { System.out.print("*"); } // print (N-1)-1 stars

// etc

In the third iteration of the outer loop, \(i=2\) and the inner loops will look like:

for ( int k = 0; k < 2; k++ ) { System.out.print(" "); } // print 2 spaces

for ( int k = 0; k < N-1-2; k++ ) { System.out.print("*"); } // print (N-1)-2 stars

// etc

And so on. In other words, the outer loop in this example controls the behavior of the inner loops.

There are one level of nesting in this example: the outer loop (the i-loop) and a bunch of k-loops. The levels of nested loops is the count of loops that contain other loops. In our example, only the i loop contains loops. The k loops do not contain any other loops.

The Restaurant example

Consider a restaurant with 36 tables, arranged in 6 rows. Each row has 6 tables. And each table seats four guests. We can write a simple report for each table, as follows:

int tableCount = 1; // initialize table counter

for ( int row = 1; row <7; row++ ) {

for ( int column = 1; column < 7; column ++ ) {

System.out.printf("Table %2d is in row %d, column %d, with guests: ", tableCount, row, column);

for ( int guest = 1 ; guest < 5 ; guest ++ ) {

System.out.printf("%2d", guest);

}

System.out.println(); // new line

tableCount = tableCount+1; // increment table count

}

}

There are two levels of nesting here: the row loop contains the column loop which contains the guest loop.

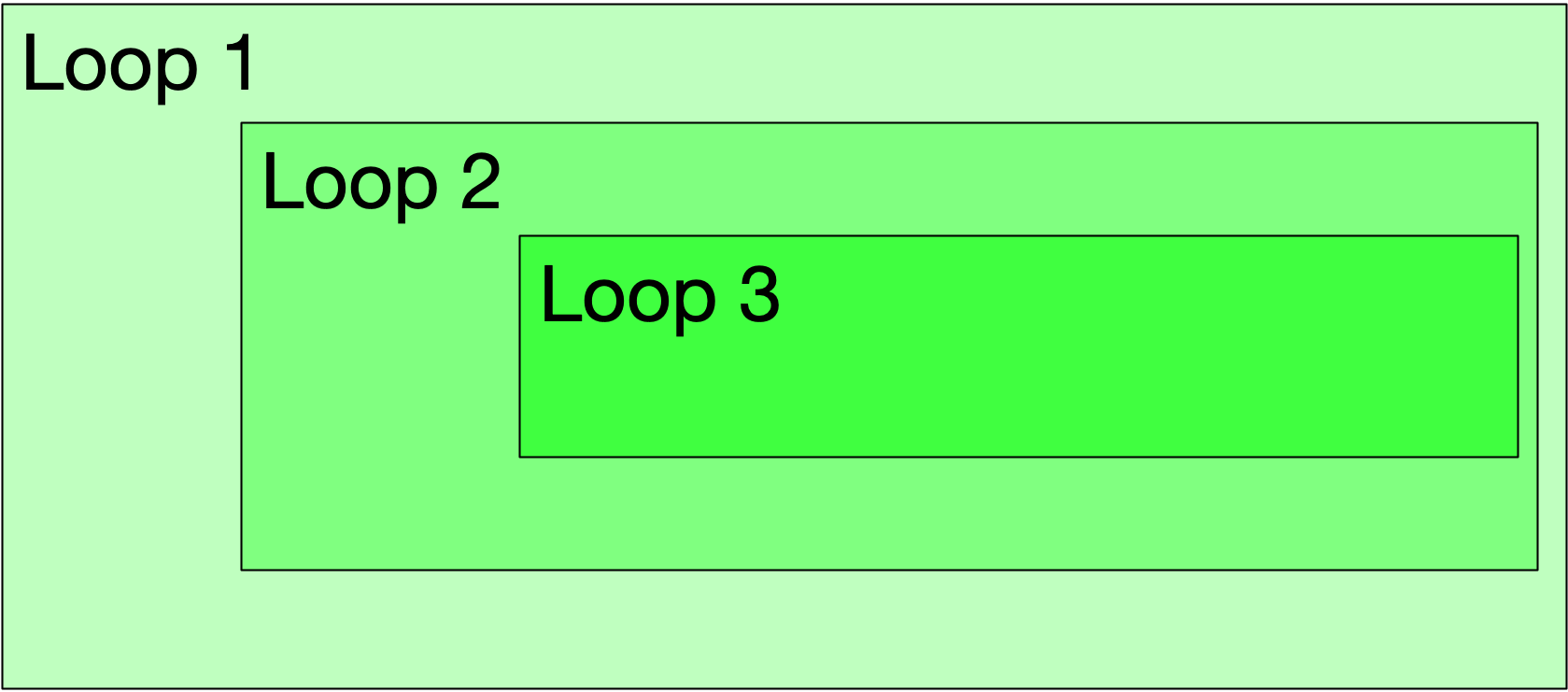

Loop structures

An example of three nested loops.

A nested loop is a loop within a loop. There is no limit as to how many loops we nest, but practically most programmers rarely go beyond 8-10 nested loops. The figure to the right shows three nested loops. A simple example of such loops is the following code.

for ( int loop1 = 0; loop1 < 10; loop1++ ) {

for ( int loop2 = 0; loop2 < 10; loop2++ ) {

for ( int loop3 = 0; loop3 < 10; loop3++ ) {

// some profound code

}

}

}

The code within the third loop will be executed \(L1\times L2\times L3\) times, where \(L1\), \(L2\), and \(L3\) are the number of steps performed by first, second, and third loop respectively.

In most loops, the number of steps is the difference between the loop’s stopping and starting value. For example, the loop for (int i=0; i<10; i++) has a stoping value of 10 and a starting value of 0. Therefore it will execute 10 steps. This estimate however, is not rigorous. The loop for (int i=0; i<=10; i++) executes 11 times, because its terminating condition includes the stoping value (\(i\leq 10\)). Also, notice that the loop for (int i=0; i<10; i=i+3) executes only 4 times, because its variable is incremented in steps of 3.

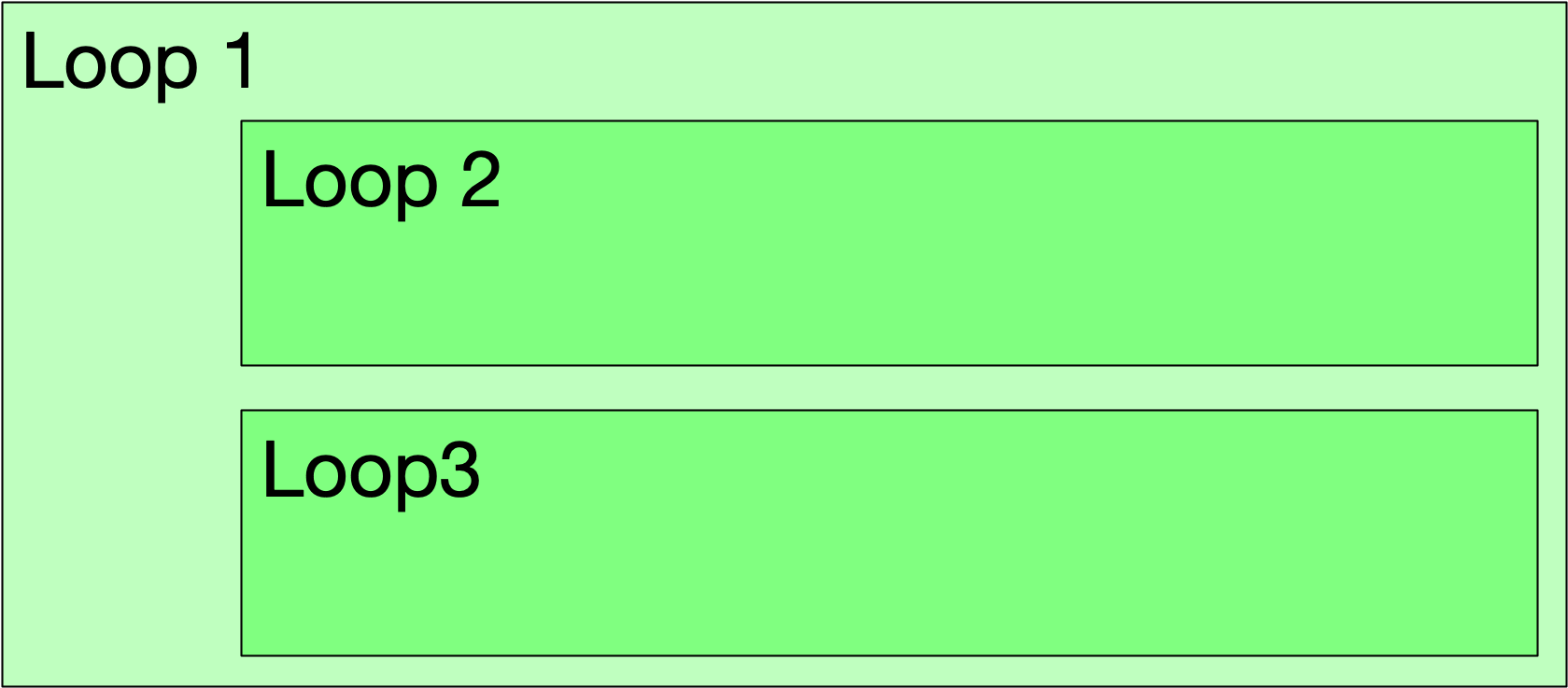

An example of two tandem loops nested in another loop.

A nested loop may contain tandem loops as shown to the right. In this case, the number of steps executed within the second loop will be \(L1\times L2\). The number of steps executed in the third loop will be \(L1\times L3\). And the total number of steps across this block of code will be \(L1\times(L2+L3)\).

A simple example of tandem loops is the following code.

for ( int loop1 = 0; loop1 < 10; loop1++ ) {

for ( int loop2 = 0; loop2 < 10; loop2++ ) {

// some profound code

}

for ( int loop3 = 0; loop3 < 10; loop3++ ) {

// more profound code following the previous profound code

}

}

For every iteration of the outer loop (loop1), the two inner loops execute one after the other. First, loop2 runs its course, then loop3. This continues until loop1 had gone through its cycle.

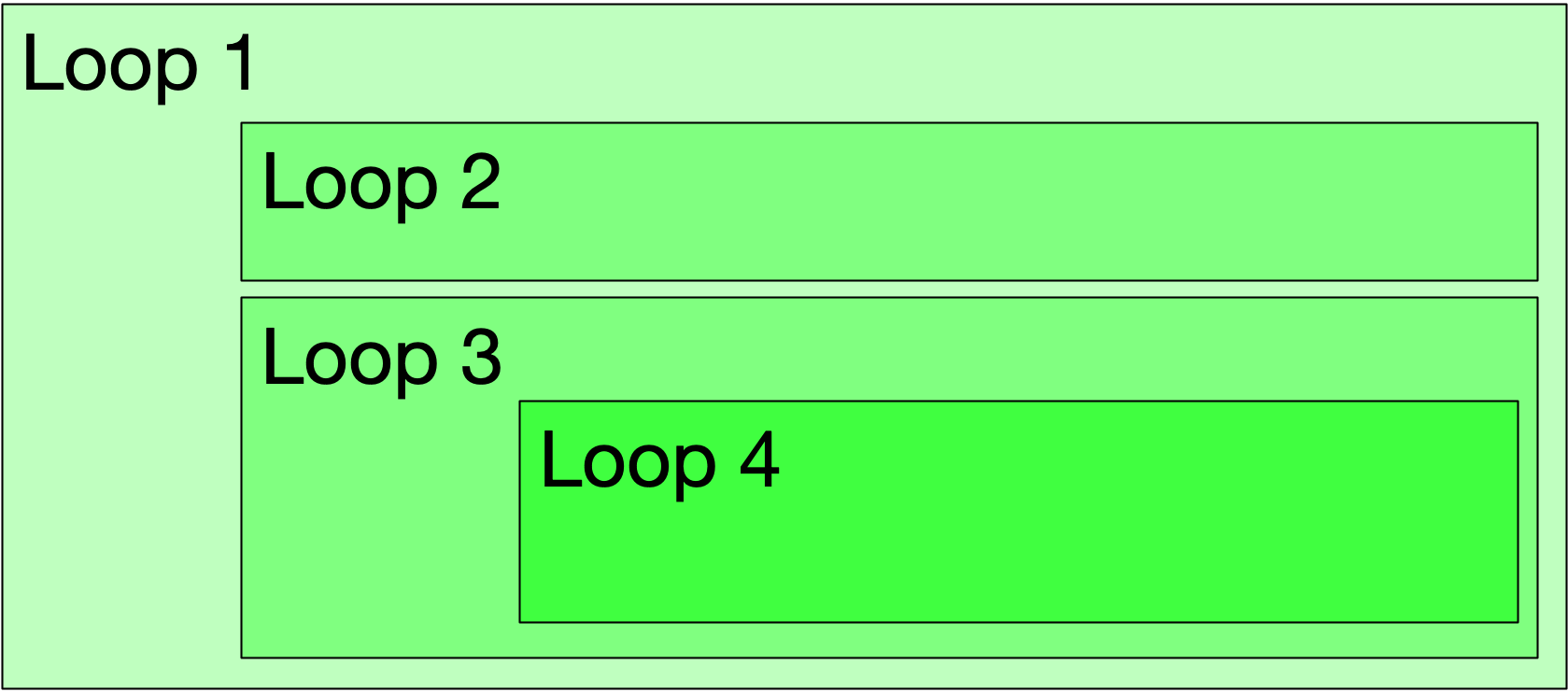

An example of two tandem loops nested in another loop, with one more loop nested in the second tandem loop.

Loops can be nested in various ways, as needed. In the example to the right, loop4 is within loop3 which is within loop1. And there is loop2 in tandem with loop3. The total number of steps taken by this combination of loops is \(L1\times (L2+L3\times L4)\). The corresponding code is as follows.

for ( int loop1 = 0; loop1 < 10; loop1++ ) {

for ( int loop2 = 0; loop2 < 10; loop2++ ) {

// some profound code

}

for ( int loop3 = 0; loop3 < 10; loop3++ ) {

// more profound code following the previous profound code

for ( int loop4 = 0; loop4 < 10; loop4++ ) {

// additional awesome code

}

}

}

Loops as hierarchical structures

The Chicago Police Department has divided the city into beats, i.e., small geographic areas that are patrolled by one police officer. The beats are numbered by four digits in the following form:

For example, the CDP car with number 1712 belongs to the 17th District (Albany Park), and patrols the district’s 12th beat. There are about 40 beats per district, though this number varies. In general, we can use a pair of two nested loops to print all patrol car numbers, as follows.

for ( int district = 0; district < 26; district++ ) {

for ( int beat = 1; beat < 40; beat++ ) {

System.out.printf("Car number %02d%02d \n",district,beat);

}

}

The code above is not fully accurate. The CPD does not have a 13th district, so we need to find a way to skip that value for loop variable district. This can be accomplished with conditional logic. In Java, such logic is implemented easily with if-then-else statements. Here’s a preview:

for ( int district = 0; district < 26; district++ ) {

for ( int beat = 1; beat < 40; beat++ ) {

if ( district != 13) {

System.out.printf("Car number %02d%02d \n",district,beat);

}

}

}

Estimating the length of a loop

It is important to be able to estimate the time that is consumed by loops. That time is related directly to the number of repetitions performed by a loop. As we saw above, we multiply the steps of nested loops and we add the steps of tandem loops. But how to tell the number of steps a loop repeats?

For simple loops, e.g.,

for ( int i = 0; i < N; i++ ) {...}

the number of steps are straight forward: \(N\). In case the terminating condition is inclusive, i.e.,

for ( int i = 0; i <= N; i++ ) {...}

the number of steps is \(N+1\).

Simple loops like those above have a well-defined starting value, usually i=0 or i=1. The terminating condition of these simple loops is also quite plain. The loops are basically counters, starting from 0 or 1 and counting up to a given number. The increment step of such loops is 1, i.e., i++ (which is shorthand for i=i+1).

Loops can have more complex definitions, however. For example, the loop

for ( int i = 0; i < N; i=i+3 ) {...}

has an increment of 3. Its variable will be \(i=0, 3, 6, 9, \ldots\). The loop will execute until it reaches that largest multiple of 3 that is less than \(N\). If, for example, \(N=10\), the loop will execute 4 times.

In a for-loop, the terminating condition usually involves the loop variable (i in the examples above). It doesn’t have too. The terminating condition of the loop is a boolean expression. The loop continues as long as this boolean expression evaluates to true, and stops when it evaluates to false. For example, how many times will the following loop run? (You may try it in JShell).

int x = 0;

for ( int i = 0; x < 10; i++ ) {

x = x + 3;

}

In all fairness however, for-loops that do not involve the loop variable in the termination condition are rather rare. Good programming practice dictates that for-loops use their variable in the terminating condition. Java offers two more loop tools, better suited for broader terminating conditions. These tools are the while-do loop and the do-while loop.